by Peter J. O'Connell

My Cousin Rachel. Released: June 2017. Runtime: 106 mins. MPAA Rating: PG-13 some sexuality and brief strong language.

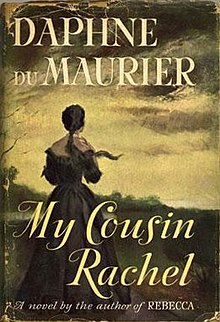

My Cousin Rachel centers around a mysterious woman—and, perhaps, the mysterious nature of women in general to some types of men. The film is directed and adapted for the screen by Roger Michell from Daphne du Maurier's 1951 neo-Victorian Gothic novel of romantic suspense.

In the mid-1800s, Philip Ashley (Sam Claflin) is a vigorous but somewhat gawky fellow in his early 20s, who lives on his family's estate near cliffs on the colorful coast of Cornwall. Philip was orphaned at age 7 and raised thereafter by his beloved older cousin, Ambrose.

The environment in which Philip was raised was rather male chauvinist. As he says at one point: “The only women allowed in the house were the dogs.” In fact, in the early scenes Philip almost seems to regard women as an alien breed, despite the fact that lovely Louise (Holliday Grainger), daughter of the family lawyer (Ian Glen), clearly is in love with him.

Having encountered some health issues, Ambrose moves to the more salubrious climes of Italy. There, he writes Philip, he has met and married a wonderful woman, a widow—Rachel. After a while, though, Ambrose's letters take on a darker tone. He suspects that Rachel is attempting to poison him.

These letters cause Philip to go to Italy, where he learns that Ambrose has died and that Rachel has left their villa. Rainaldi (Pierfrancesco Favino), an Italian lawyer, tells Philip that doctors suspected that a brain tumor killed Ambrose and had made him paranoid before his death.

Philip, however, chooses to suspect Rachel and vows: “Whatever it cost my cousin in pain and suffering before he died, I will return with full measure upon the woman that caused it.” He remains angry, even though Rainaldi tells him that Ambrose left his estate to Philip—rather than to Rachel—to be kept in trust until Philip turned 25.

After returning to England, Philip is stunned to learn that Rachel is coming to pay him a visit at the estate in order to return some possessions of Ambrose. In keeping with his vow, Philip is at first hostile to Rachel, but soon falls under the spell of her youth, beauty, and the kindness that she sets about showing him. Apparently, the fact that Philip is virginal makes him swoon readily for someone as appealing as Rachel, despite his male chauvinist upbringing. Philip even, like Romeo, climbs up the outside of the mansion one night in order to enter Rachel's room.

Like some noted mid-Victorian novels, du Maurier's tale, published in 1951 but set a century or so earlier, has much financial and legal maneuvering interacting with its darkly romantic plot. Did Ambrose actually intend his estate to go to Philip or to Rachel? Is it wise for Philip to give Rachel a generous allowance? What is the the real nature of the ties between Rachel and the Italian lawyer, who is spotted in England?

Complications are added to those questions by some surprising turns in the relationship of Rachel and Philip, turns that cause the smitten Philip to revert to male chauvinism. But isn't that wrong of him in view of Rachel's care for him when an illness strikes? Apparently, the “special tea” that she makes isn't a poison. But what about those unquestionably poisonous seeds in her room?

The film, literally, gallops to a very dramatic climax. The movie began with Philip saying in voiceover: “Did she? Didn't she? Who was to blame?” And it ends with Philip saying: “Rachel, my torment.” Audience members will, undoubtedly, have varying responses to make to these exclamations.

Audience members also will, undoubtedly, have varying opinions of the quality of the film, most likely largely based on evaluations of the performances of Claflin and Weisz in their roles as scripted. Claflin provides a vigorous, yet gawky, rendition of the vigorous, yet gawky, Philip. But shouldn't it have been a highly skilled rendition, such as Richard Burton's Oscar-winning turn in the 1952 film version? Rachel Weisz is good as the “good Rachel,” but perhaps not so good at projecting that frisson of ominous ambiguity suggesting that the blackclad beauteous widow may also be a “black widow.” Aside from issues about his direction of Claflin and Weisz, Michell provides a fine supporting cast and striking settings.

No comments:

Post a Comment