by Peter J. O'Connell

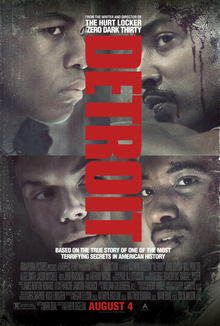

Detroit. Released: Aug. 2017. Runtime: 143 mins. MPAA Rating: R for strong violence and pervasive language.

Detroit, directed by Kathryn Bigelow and written by Mark Boal, is a film of scope and scale, style and significance—and one of great sadness. It is both a history lesson and a horror story. The lesson is about the multiple ways that racism leads to horrible events. The story is the true one that has become infamous as the “Algiers Motel incident.”

The film begins by showing a sequence of Jacob Lawrence's wonderful paintings depicting the “Great Migration” of Southern blacks to Northern cities around the time of World War I. One of those cities was Detroit, which became a mighty metropolis known as “Motor City.” But, as on-screen text explains, after World War II another migration—that of whites to the suburbs—took place. The black community of Detroit found itself left behind in poverty, with substandard housing and schools—but an almost all-white police force, many of whose members were prejudiced..

Frustration built up and erupted into violence one sweltering night in July 1967. Police raided an unlicensed club where a party celebrating the return of black veterans from Vietnam was taking place. Instead of simply closing down the venue and sending everyone home, the police insisted on treating all the partygoers as criminals, arresting them, and transporting them to lockup. Delays in transporting the arrestees allowed an angry crowd to gather. Someone shouted out: “What did they do?”

Bottles, rocks, and Molotov cocktails were thrown. Looters broke into stores. Fires were set. A full-scale riot soon engulfed much of the city. Black leaders attempted to calm the crowds, but to no avail. Governor George Romney and President Lyndon Johnson called out state police, the National Guard, and federal troops to help the Detroit police quell the rioting, as days passed.

Bigelow brilliantly mixes actual footage of the riot and reenactments in such a way as to plunge the audience members into the midst of the chaos and make them feel as jittery as the camera work on the screen. One wonders how such disparate events will be brought together as: the shooting to death by Krauss (Will Poulter), a baby-faced cop with Seussical eyebrows, of a black for stealing two bags of groceries; the peacemaking efforts of Dismukes (John Boyega), a black security guard; and the disappointment of the Dramatics, a promising young R&B group slated to perform after Martha and the Vandellas at a theatre, who find the show cancelled because of the riot just as they are about to go on. Movingly, the group's lead singer, Larry (Algee Smith), sings beautifully to the empty theatre before leaving.

The characters in these various events come together at the Manor House of the Algiers Motel, an oasis of relaxed poolside socializing in the midst of the burning city. Larry and a friend make their way there, where they meet several more young blacks and two young white women from Ohio, one, Julie (Hannah Murray), the daughter of a judge.

The atmosphere at the Algiers changes with shocking suddenness when Carl (Jason Mitchell), a young black man fooling around with a starter pistol fires off some blanks. His horseplay causes gunplay. Police and National Guardsmen nearby think that they are being fired upon, unleash a blizzard of bullets against the Algiers, and raid the Manor. One of the cops is Krauss, accompanied by Flynn (Ben O'Toole) and Demens (Jack Raynor). Dismukes is on duty across the street and goes over to the Algiers to witness the night's events.

The police raid soon becomes, in effect, like a home invasion, with tormenting of the residents as Krauss takes charge, acting out of a mix of paranoia, power-madness, racism, and sadism. He says to the blacks: “I'm just gonna assume you're all criminals.”

The cry from earlier in the film now becomes the leitmotif of the gripping action. “What did they do?” That is, what did the blacks do to deserve the evils being inflicted upon them? Yes, Carl was irresponsible, but the police overreaction is horrendous.

Before the night is over, three black men have been murdered; seven more black men and the two white women have been brutalized; and one of the white women has been stripped naked. No, not every white is depicted as an active evildoer. Some disapproving ones show up at the scene, but leave rather than, as one says, get “involved in a civil rights mix-up.”

The last part of the film shows in brief, but moving, scenes and on-screen text the “justice”--not--meted out to the perpetrators of the Algiers Motel incident and the trauma of the survivors and the families of the dead. So sad.

Bigelow has gotten uniformly excellent performances from her cast. Poulter as Krauss is riveting. Algee Smith as Larry and Anthony Mackie as a brutalized Vietnam veteran are, too, and much of their fine acting has to be done while their faces are pressed against a wall! Ben O'Toole as Flynn is a brooding presence, seldom speaking but occasionally erupting into violence. Hannah Murray is appealing as a young woman trying to be brave while being degraded. And John Boyega conveys well the conflicted situation of Dismukes, the only black in uniform at the Algiers.

Bigelow and Boal's wrenching and thought-provoking film ends by telling us that though Larry was too traumatized to ever perform again with the Dramatics, the group itself continues performing to this day. The Motor City never recovered from the riots of 1967, and the Algiers Motel and its Manor have long since been torn down, but at least the Motown melody lives on. Tragically, so does the malady of racism.

No comments:

Post a Comment